For nearly one hundred years–between the 1880’s and the 1960’s a stretch of the Hudson Valley in upstate New York was known as the “Violet Capital of the World.”

For nearly one hundred years–between the 1880’s and the 1960’s a stretch of the Hudson Valley in upstate New York was known as the “Violet Capital of the World.”

Herb Saltford recounted that it was his grandfather, William Saltford– head gardener at several estates in England before the family moved to Hyde Park, New York– who introduced the cultivation of English violets to the Northeastern U.S. in 1882. Hundreds of greenhouse operations were once situated along Route 9g from Hyde Park through Rhinebeck and up to Red Hook; this major thoroughfare is still referred to as “Violet Avenue.”

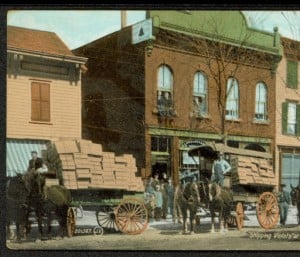

Most were sent to the nearby residents of New York City, but Hudson Valley violets were shipped as far as the Mississippi River. Violet corsages were considered essential for Valentine’s Day; they were also preferred for bridal bouquets before Lily of the Valley replaced them.

In the early 1900’s violet corsages were sold on the street corners and in the flower shops of most metropolitan areas. They were de rigeur for Yale football games and Easter Parades everywhere. Chorus girl, Evelyn Nesbitt, wore violets on her hat each day she attended her husband’s trial for the murder of her lover, the architect Sanford White. Even during the depression, when ordinary people couldn’t afford them, champions of the violet corsage ranged from Mrs. Vincent Astor to Ava Gardner, and none was more steadfast than Eleanor Roosevelt of Hyde Park, who wore them to every presidential inaugural and received weekly deliveries while in the White House.

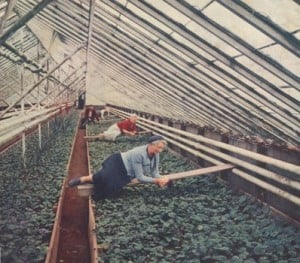

At its height, nearly twenty percent of the surrounding population was involved in some way in the Hudson Valley violet industry. Inside glass greenhouses heated with coal, the violets grew in beds in the ground. Flower pickers lay on wooden boards suspended above the plants to harvest them. It is said that a fast picker could pick five thousand flowers a day. The harvested flowers were bunched and wrapped together temporarily with string. In the packing house, the bouquet was finished with a skirt of heart-shaped galax urceolata * leaves and a “boot” to keep it moist.

At its height, nearly twenty percent of the surrounding population was involved in some way in the Hudson Valley violet industry. Inside glass greenhouses heated with coal, the violets grew in beds in the ground. Flower pickers lay on wooden boards suspended above the plants to harvest them. It is said that a fast picker could pick five thousand flowers a day. The harvested flowers were bunched and wrapped together temporarily with string. In the packing house, the bouquet was finished with a skirt of heart-shaped galax urceolata * leaves and a “boot” to keep it moist.

By 1914, black rot had become a problem for many growers. Disinfection of both the soil and the wooden structures was necessary to eradicate it. In addition, women’s clothing had become lighter, less suited for pinning a corsage to. By 1956, only fifty to sixty greenhouses remained. And in 1979, Eugene Trombini announced the closing of the last one. His business alone had once grown six million plants in eighteen greenhouses.

*It was not unusual for residents of rural Appalachia and the Carolinas to harvest the leaves of this native evergreen groundcover for sale to the floral industry at this time, and the practice continues today.