In an increasingly uncertain world, food security is high on the national agenda – but sowing, growing and saving our own seed sparks a virtuous cycle that lets gardeners take back control.

What if I told you that the adaptability and resilience we’ll need to navigate the growing uncertainties in a future of profound climatic and ecological change could be found in… a seed packet?

Puzzled? How about if I throw in that, with a modicum of enthusiasm and determination, you will never have to buy some types of seed ever again? Intrigued? And what if I said that you, me and every other gardener across the land can each do our bit to help cultivate a more resilient, food-secure future? Are you ready?

Wales Seed Hub/Hwb Hadau Cymru is a hotbed of horticultural resilience. It’s a co-operative of small growers from across Wales who have joined forces, using agroecological practices (that’s blending ecological principles with agricultural techniques), to collectively grow, packet, market and distribute their own seeds (each grower focuses on specific crops). But these are not just any old seeds; the carefully selected varieties they offer are proven to do well in our damp and fickle Welsh climate (hooray!), are not widely available elsewhere, and often have a Welsh backstory. The Hub doesn’t buy in seeds to sell on.

But here’s the best bit: they are all open-pollinated varieties, meaning anyone can save seeds from their own vegetables and flowers, which they can sow again (and again and again) to get essentially the same plants. This repeated sow/save cycle is how resilience becomes embedded in your own seeds; they adapt to the specific growing conditions found in your garden, greenhouse, polytunnel, allotment and local area.

One of the Hub’s core aims is to get its seed out into as many gardens – especially Welsh gardens – as possible, then encourage us all to grow our own (constantly adapting) plants, save the seeds, and then share those seeds, encouraging others to continue the chain of sowing and saving.

This is the real deal when it comes to ‘taking back control’. Saving our own seeds not only reduces our reliance on large seed companies, it trims resource use, saves us money (hybrid, cross-pollinated F1 seed is pricey), and sows inside us something money can’t buy – a sense of soil-under-the-fingernails empowerment. It’s akin to taking out countless insurance policies across the land; if one seed saver’s crop fails, due to an extreme weather event such as flooding, there will be many others which go on to successfully produce viable seeds to perpetuate the sow/save cycle.

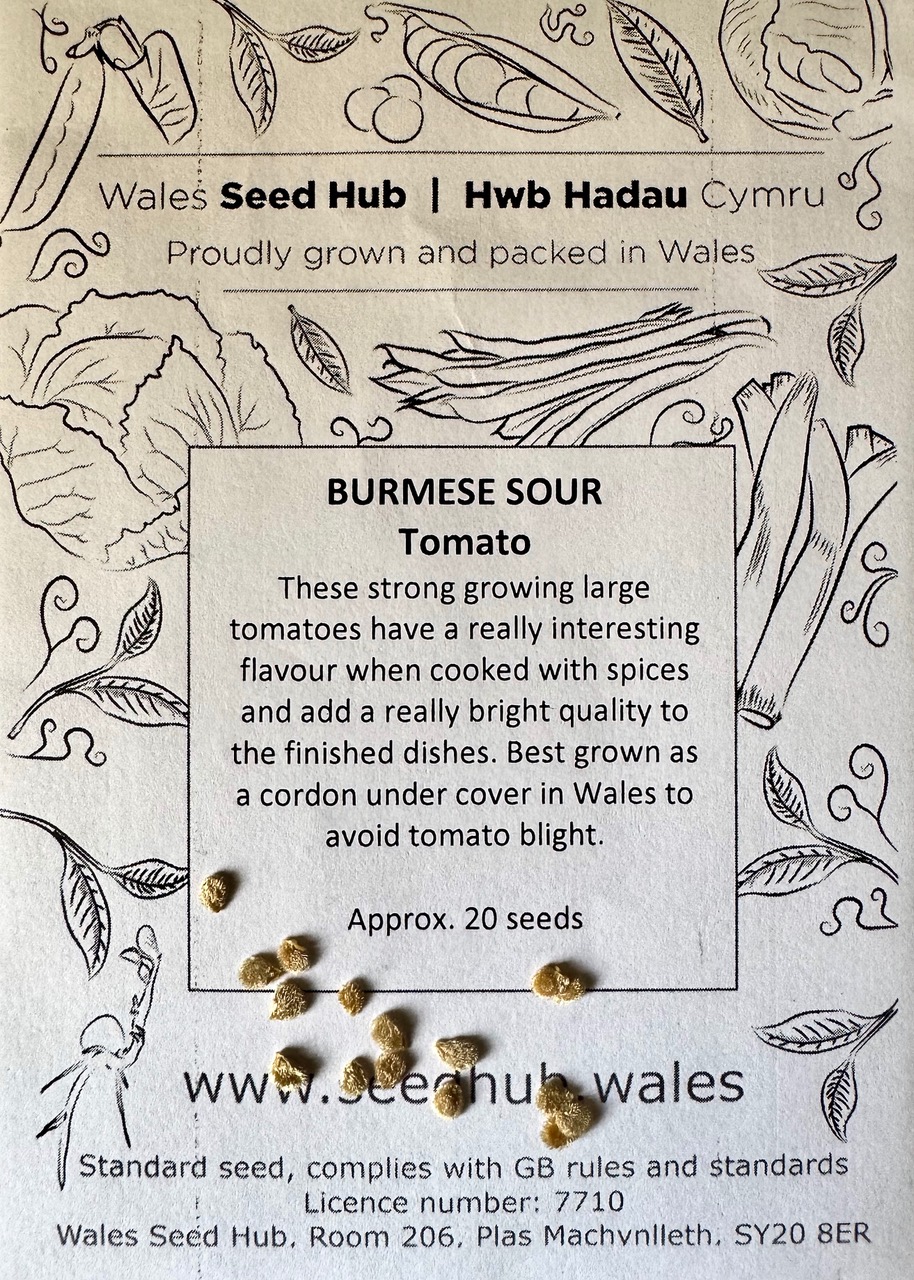

I’ve ordered all of the Hub’s 10 tantalising, tomatoholic-tempting varieties – with names like ‘Burmese Sour’, ‘Gardener’s Ecstasy’ and ‘Warsaw Raspberry’, who could possibly resist? – to grace my greenhouse this summer. My plastic-free, everything-is-compostable package of seeds also contained encouragement to begin my own sow/save journey, by way of a set of 10 colourful seed-saving postcards, giving clear advice for all of the vegetables the Hub sells.

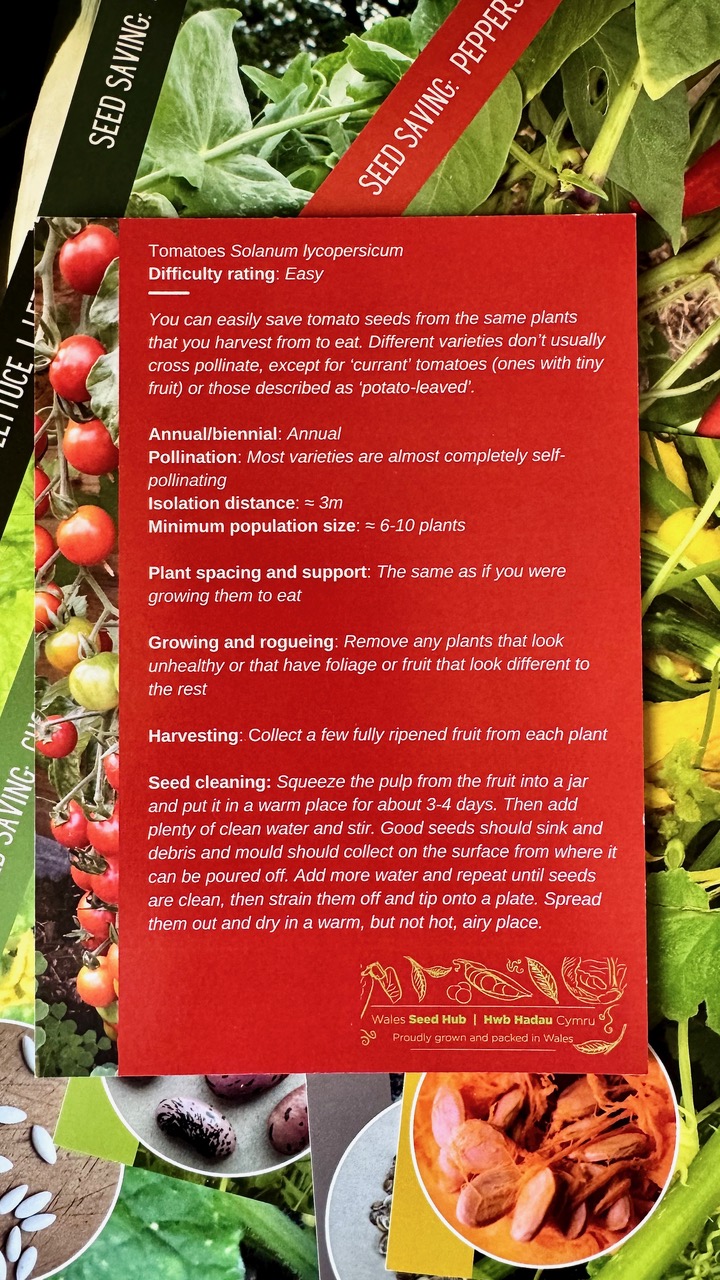

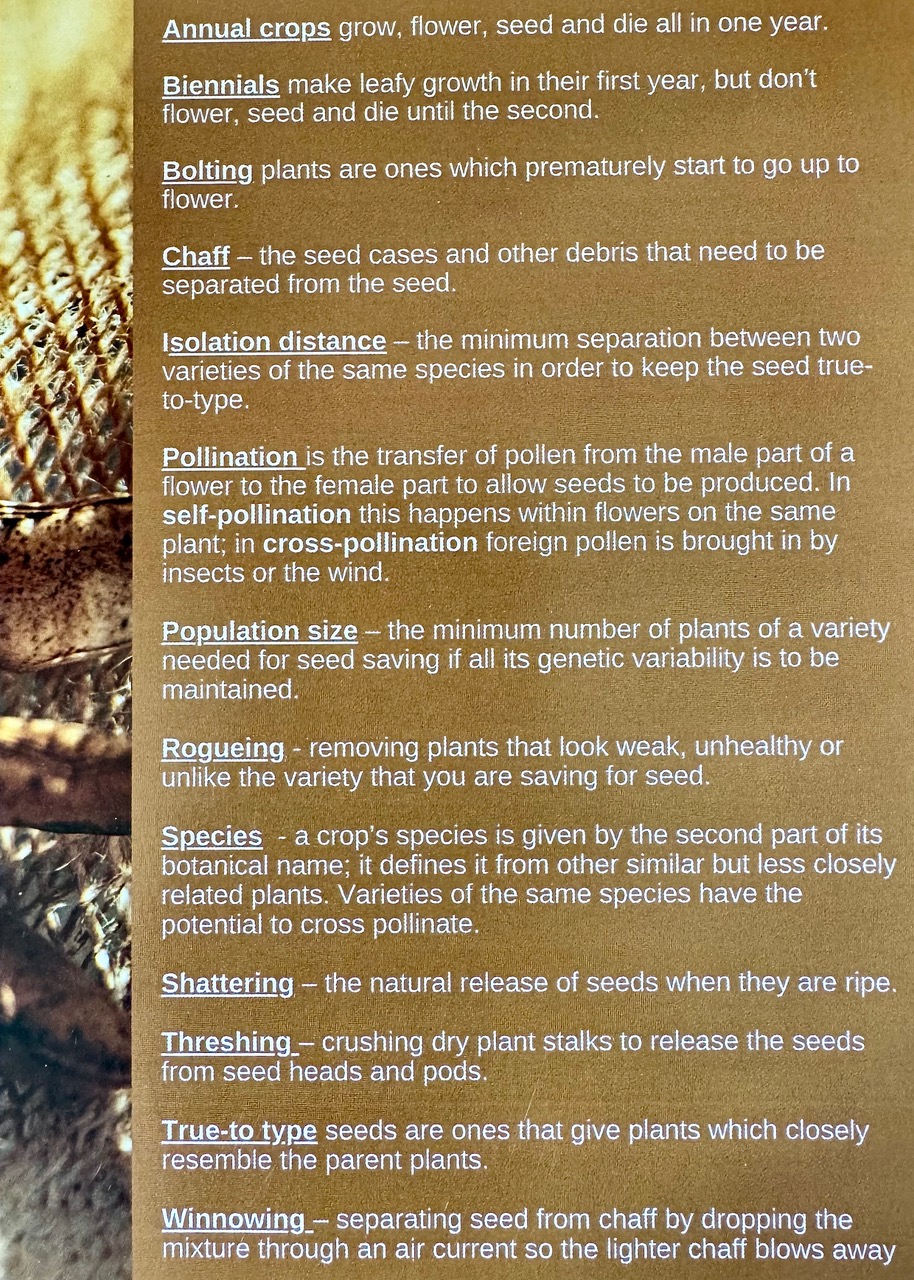

One card is a useful seed-saving glossary, explaining in plain garden-speak terms such as ‘rogueing’, which is removing odd-looking and unhealthy plants, ‘threshing’ of dry stalks to release seeds from pods and seedheads, and ‘winnowing’ to separate the seeds from the chaff by dropping them through a light breeze. Each individual crop card has information particular to that plant. Eyeing the difficulty rating for saving tomato seeds as ‘easy’, I knew this was the crop for me.

Most tomatoes pollinate themselves. Their blooms have very short stigmas deep within the flower, which can only be fertilised by pollen from the anthers of the same flower. Insects can’t reach into the flowers, so there’s no cross-fertilisation by pollen from nearby plants. I’ll be able to save seeds from the same fruits I pick to eat.

Harvesting tomato seeds is the fun and gooey bit. Squeeze the seeds and juice into a jar and put it in a warm place to ferment for three days, stirring daily, until it goes mouldy and pongs (this breaks down the jelly-like coating on each seed and kills off seed-borne diseases). Next, fill the jar with water and stir, separating the good, viable seeds (which sink) from the mould and any floating seeds. Rinse the good seeds in a sieve, then put them on a shiny plate to dry in a warm place.

In contrast, parsnips (the Hub sells ‘Student’, a heritage variety) are rated as difficult. To produce seeds I’d need to grow 20 to 50 plants of the same variety with an isolation distance from any other parsnips of 500m to 1,000m. That’s some undertaking – you would need to be entirely surrounded by non-vegetable-growing neighbours, or ask those growing veg to all grow the same variety as you (parsnips are cross-pollinated by insects such as hoverflies), or do your sowing/saving deep in parsnip-free countryside… The Hub’s website offers clear, tip-rich guidance on other trickier-to-save seeds, such as chillies, peppers, cucumbers and squash.

There’s a fine way to demonstrate that resilience really can be home-grown. Imagine that all 20 of my ‘Burmese Sour’ seeds germinate. I could gift most of the young plants to fellow gardeners, along with copies of the Hub’s seed-saving cards and glossary, all bundled in with enthusiasm and encouragement. If only a handful of my fellow tomatophiles decide to have a go at seed-saving, that’s potentially thousands more seeds of ‘Burmese Sour’ (or any other open-pollinated variety) being sown and shared by the hands of other keen, determined gardeners, keeping the ever-adapting sow/save cycle growing.

Resilience resides in a single packet of seeds. Shall we?

Text © John Walker. Images © Wales Seed Hub/Hwb Hadau Cymru

Join John on X @earthFgardener